In the seventh installment of the Florida Courier’s series on Blacks and mental health, we learn that progressive churches are building partnerships with state government and ‘secular’ organizations to bring mental health care to people in need.

BY JENISE GRIFFIN MORGAN

FLORIDA COURIER

A comprehensive plan is in the works that could provide faith-based mental health treatment to scores of worshippers at African-American churches in Jacksonville. – This story originally appeared in the Florida Courier on May 23, 2014.

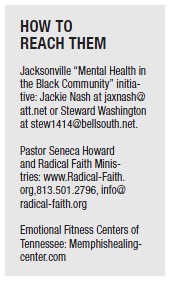

The plan was rolled out on May 16 during a “Mental Health and the Ministry” workshop at Edward Waters College that was part of a three-day 32nd Annual Conference on Mental Health and the Black Community sponsored by the Northwest Behavioral Health Services, Jacksonville Association of Black Psychologists and the Jacksonville chapter of the National Association of Black Social Workers.

The team of licensed social workers and mental health counselors working on the project are hoping it will remove barriers to diagnoses and treatment among parishioners in the African-American church.

“Most churches have health ministries and we want them to incorporate behavioral health into their health ministries,” said Jackie Nash, a retired licensed clinical social worker who spoke at the workshop. “We will provide training so they will know how to address the issues from a layman’s point of view. We’re not asking them to do professional stuff.’’

An ‘altar alliance’

The plan calls for faith-based counseling and treatment to be provided by a network of partners, including trained chaplains, clinical pastoral counselors and mental health providers.

For the past two years, Nash and Steward Washington, a licensed mental health counselor, have examined health ministries of small and large churches in the Jacksonville area. They have identified about 900 churches in two zip codes in New Town, described as a traditional African-American working class community.

Nash said two of Jacksonville’s large churches that already are providing behavioral health services to their congregations, the Potter’s House and Bethel Baptist Institutional, have been major supporters. Others on board include the state Department of Children and Family Services, the Casey Foundation and the Family Support Services of Jacksonville.

Nash and those involved in the project also are hoping to attract local, state and federal funding to cover the cost, which would include training health ministry teams at area churches to recognize signs and symptoms of mental illness to improve health outcomes of congregants.

Scarce funds

According to the Jacksonville Community Council, a non-profit think tank that is conducting a mental health study, Northeast Florida is one of the most poorly funded regions in Florida. The council states that advocacy is critical to secure more funding for those who need treatment.

Nash said more churches are accepting a more responsible role in providing treatment. This shift negates the historical approach that encouraged members to primarily rely on kneeling before spiritual altars to heal psychological affects, including clinical depression and schizophrenia. Suicide and broken lives are the statistical sad results.

Not equipped

Nash shared that that many of the churches are just not equipped to help their members deal with behavioral health issues.

“I believe totally in prayer. I also know God has put in place other things to help prayer do what it needs to do,” she remarked.

Faith-based organizations are beginning to recognize that in addition to services of private and not-for-profit mental health providers, they too must provide a full range of programs and services to prevent and treat mental illness, stated Vernon Washington, a local clinical counselor and minister who presented the plan to the pastors, lay leaders, community leaders and others attending the workshop held at Edward Waters College.

“The partnerships with local, state and federal agencies is designed to use a faith-based approach to increase public awareness regarding treatment availabilities for community-based mental health services,’’ he related.

Conflict of interest?

Embarrassment and fear of a confidentiality breach are two factors that cause congregations to suffer in silence. African-American church leaders typically make counseling available with spiritually equipped ministry leaders, but that training rarely equates to the professional expertise of a clinical psychiatrist or licensed mental health worker.

“We have people sitting in congregations who have mental health needs, and I’m a believer,” added Vernon Washington, who also is a minister. “They are believing that God will solve all of their problems without any intervention from an outside source, and that is simply a misconception of what God is.”

The minister says he doesn’t believe pastors should counsel members of their congregation, calling it a conflict of interest.

“I believe counseling has gone off track in the church because people are not prepared, not trained,” he remarked.

Nash points out that their goal is to “create an environment of healing within the church and community that equips and fosters wholeness of mind, body and spirit.”

She acknowledges that many Blacks still are concerned they are going to be called “crazy” if someone learns they are seeking help. Nash adds that’s the reason it is important for churches to have people who don’t gossip working in their health ministries.

“There is still a stigma there and there’s a lot of education that will have to go on to get where we need to be,” she added.

Success in Tennessee

While Nash and others are getting their program off the ground, a network of Black churches in West Tennessee have had success providing mental health – or as they call it, “emotional healing” – success for years.

In 2006, the state of Tennessee began to explore ways to get people into mental health treatment, said Pastor Dianne Young of the Healing Center Full Gospel Baptist Church in Memphis.

After much discussion, many meetings and research it was found that in West Tennessee, particularly among African-Americans, it would take a trusted organization “to sound the alarm, advocate and promote mental health services,” said Young, whose husband, Bishop William Young, is the senior pastor of the Healing Center.

The church already was providing services through its Healing Word Counseling Center.

From mental to emotional

However, the Youngs developed a partnership with the state and became co-founders of the Emotional Fitness Centers of Tennessee. The name, she said, made it friendly to potential clients.

“In the Black community, historically needing mental health care meant you were ‘crazy’ so this need would be ignored and unmet. With the birth of the Emotional Fitness Centers of Tennessee, removing the word ‘mental’ and repackaging the services, an emotional fitness screening – though it is a mental health screening – is viewed as another checkup, an additional way of living a healthy life.

The name helped remove stigma and calm fears associated with need and mental health services,” she explained.

Ten African-American churches now have Emotional Fitness Centers on their sites. Each church has one to four peer advocate liaisons at each site, a licensed professional counselor, a program manager and a navigator.

Oversight of the project is the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Young noted.

Thousands screened

Since January 2008, the centers have screened about 4,000 people and more than 2,000 have followed through in getting the needed care. Treatment is free due to a grant provided through the state.

The centers have more than 25 partners, including mental health centers, drug and alcohol treatment centers, hospitals and other local and state agencies.

Each year, the Emotional Fitness Centers of Tennessee hosts a grief and remembrance event for families that have experienced losses; conducts emotional fitness fairs; and biannually co-hosts the National Suicide and the Black Church Conference.

Added Dianne Young, “The dream is to see emotional fitness screenings become a part of our annual checkup and this ‘best practice’ move across the state and Tennessee become a model for the nation.”

Florida pastor’s initiative

Back in Florida, a Tampa pastor is gearing up for a “Mental Illness and the Church” online workshop set for June 5-July 24.

The workshop is hosted by Pastor Seneca Howard of Radical Faith Ministries, who also lives with mental illness. Howard, 29, told the Florida Courier that he was diagnosed as a child with borderline intellectual functioning, formerly referred to as borderline mental retardation.

“Living with this condition does not control your destiny. I overcome daily, and I fully intend to share my story, provide guidance and encouragement to others and help provide useful tools to help others overcome daily and reach their full potential,” he states.

His workshop, which includes biblical references to mental illness, includes professionals who discuss such topics as the six stages of grief, chemical imbalances, the effects of mental health disorders on a child’s education, and suicide.

Last year, Howard led a 13-week series on mental health at his church. In September, he plans to offer another brick-and-mortar workshop on the subject.

Jenise Griffin Morgan, senior editor of the Florida Courier, is a 2013-14 fellow of the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism. She can be reached at Jmorgan@flcourier.com.